What a 2D artist does in mobile game development

Artwork for a mobile project goes through the same pipeline as it does with desktop AAA games: dozens of sketches, different angles, detailing, working with color, and so on. The metrics and the project’s success largely depend on the quality of work — in other words, it’s never easy.

Most of our 2D artists are generalists who independently go through every production stage: looking for references, making sketches, concepts, and rendering materials. If necessary, they can draw an icon, a banner, or some screenshots for the store.

Projects are constantly changing. First, you draw sci-fi stuff for Space Armada, then pirate ships for King of Sails, and then big mechs for Robot Warfare. Artists have to constantly learn new styles and genres.

To better showcase the workflow, let’s go through the stages of creating artwork for mid-core projects.

1. Choosing a visual style

The project’s style (cartoonish, realistic) and setting (cyberpunk, fantasy, sci-fi, etc.) are usually established in the first game design documents. Drawing them up is a team effort: game designers fill GDDs with semantic content and pass them to the artists who propose different options for the visuals by putting together initial references.

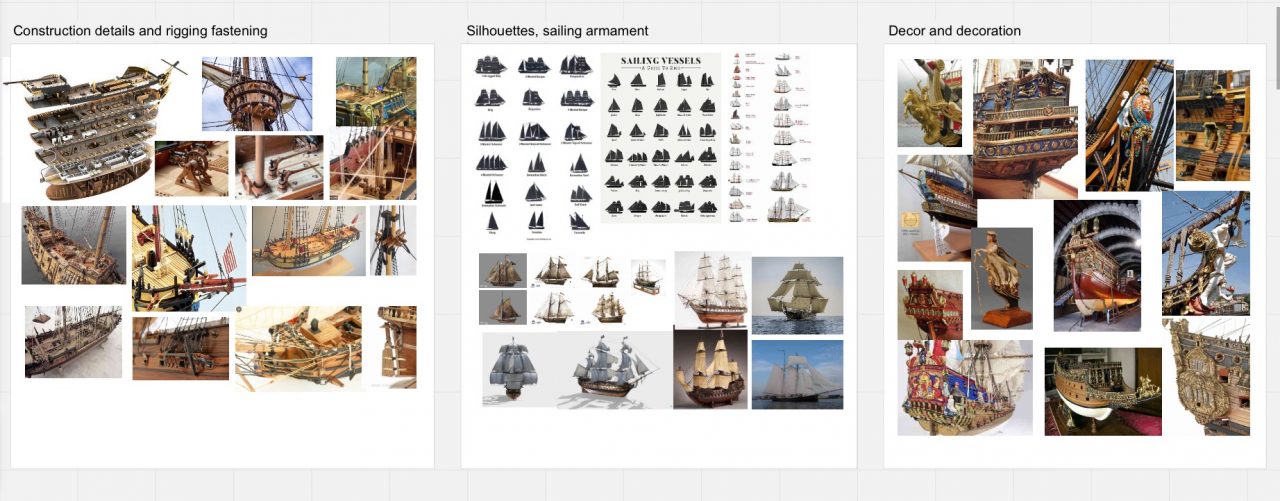

Plenty of development stages require references. For this specific one, the artist gathers information on popular styles within various settings. To approve the nuances, sometimes you need separate moodboards in the following areas: mood, atmosphere, colors, silhouettes, and others. After the direction is agreed upon, the collected references become the foundation for the initial artwork.

If necessary, the artist draws the same scene in several visual styles. Even at this point, the artwork goes through the entire pipeline — from the sketch to the colors and materials — and this is just the first stage.

The resulting artwork can also be used as fake shots (screenshots of a non-existent game). With their help, you can launch marketing campaigns and check ideas for viability even before you start working on the first prototype — if users click on an ad creative a lot, you can start thinking about sending the idea to production. This method is more suitable for indie developers and small studios, we rarely use it at Azur Games. Basically, the artwork is required internally, for the team to visualize the differences and form a common vision of the final picture for the project.

2. Forming the basic principles of artwork composition

At this stage, fundamental art principles are laid down, and clarifying references are collected. Before creating concepts, based on the game designers’ request, the artist collects information about the subject of development (design features, decor, etc.) and establishes the main characteristic features and visual differences at the background level.

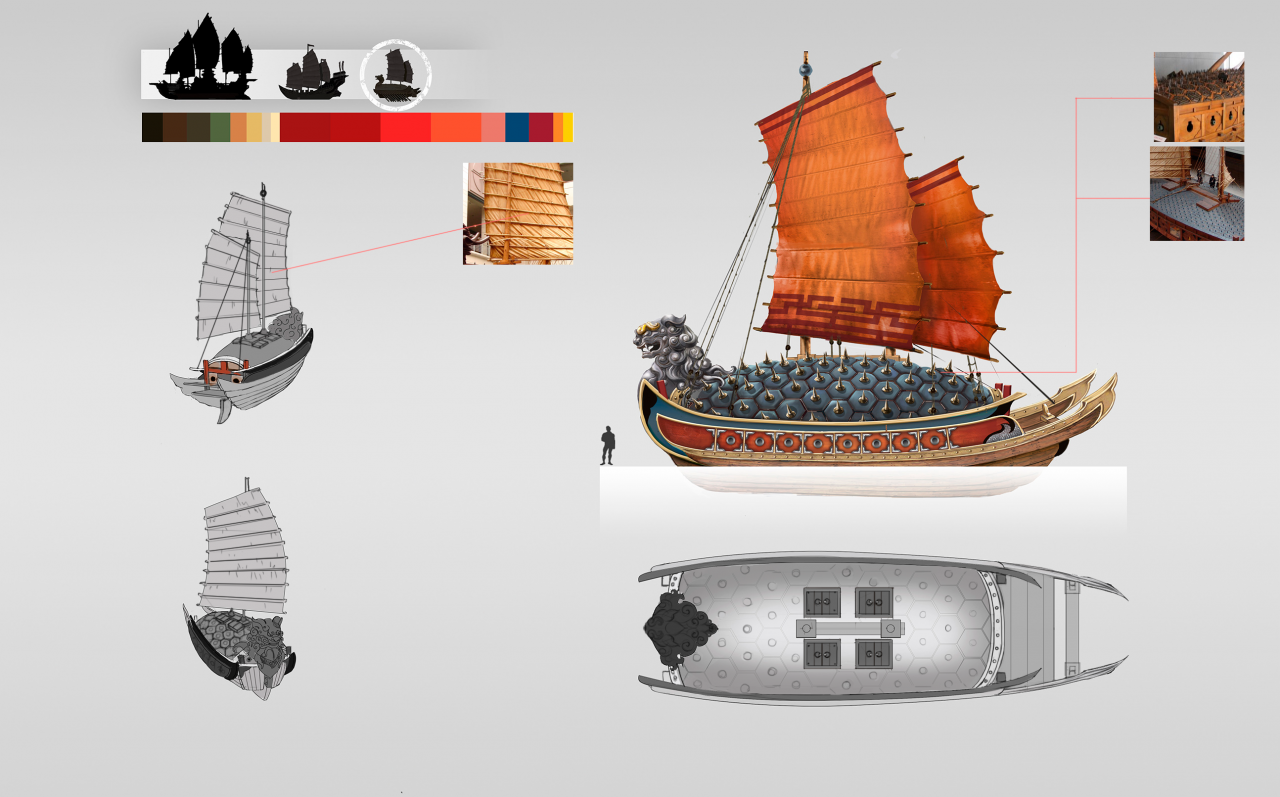

For example, King of Sails, a 3D game about battles on old ships in a realistic setting, was set to have several factions from the very beginning. It was necessary to lay down visual distinctions so that the ships could be told apart from afar, and each faction is unique in silhouettes and colors.

All this means extensive research work. The artist looks at hundreds of sailing ships, finds interesting models that fit the mechanics, forms an art selection, and then breaks everything down according to unique faction features: black, armored ships with spikes and metal, red ones with gold and a special sail design, and so on.

All future concepts are created according to these established principles and rules.

3. Sketches

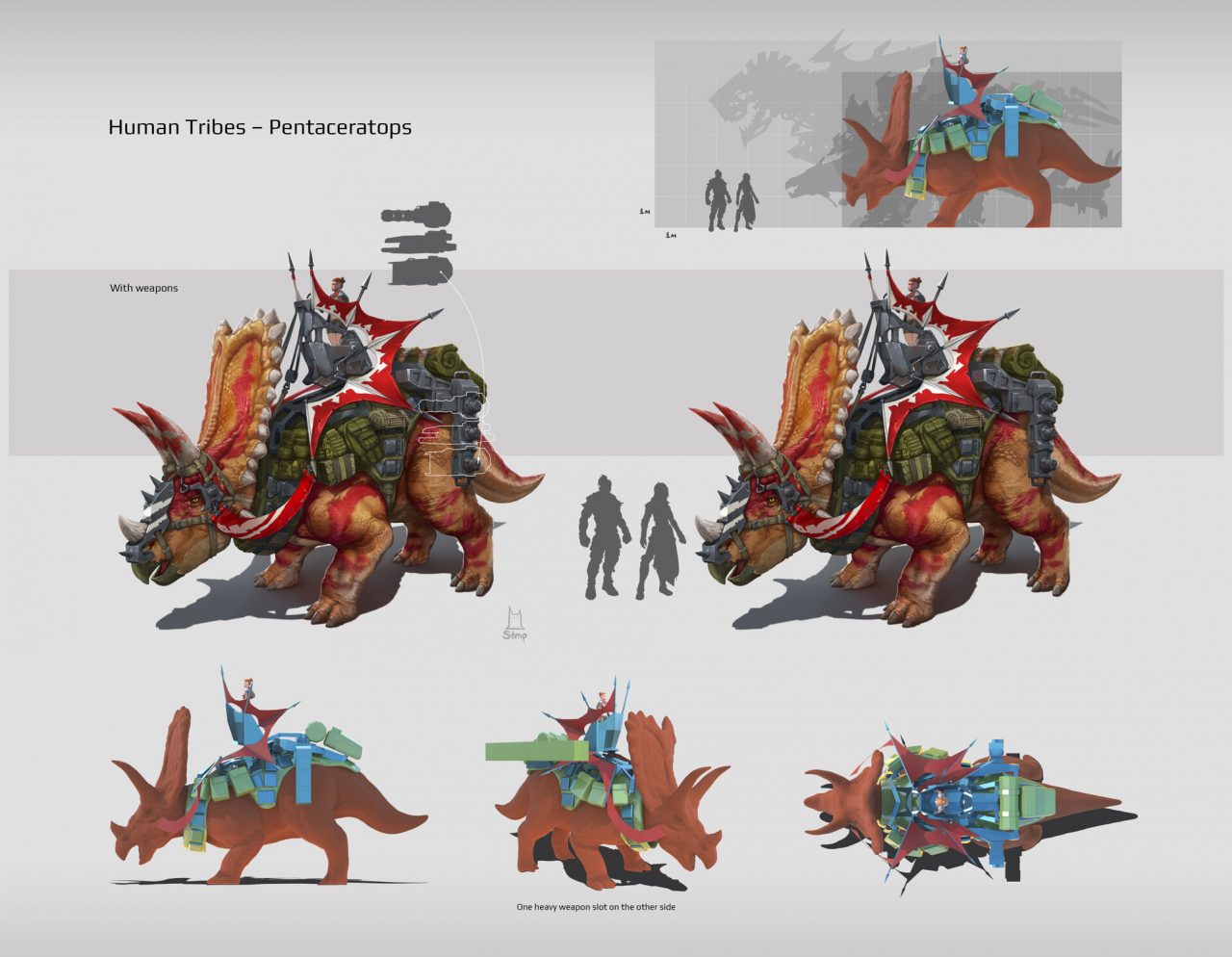

Artwork creation begins with sketches — a quick sketch in b/w without detailed elaboration. Here, the model’s silhouette is the priority.

Every project has its specific traits. In King of Sails, each faction should have a light, medium, and heavy ship. Therefore, they need to be connected through a common visual style and separated in terms of UX so that the player immediately understands which ship is in front of them. This is also the artist’s creative responsibility.

Also, due to the design features, we simultaneously drew sketches for all ship classes within the faction, so they wouldn’t turn out similar later.

A mid-level 2D artist draws one sketch in 30 minutes, approximately 7-14 sketches for each model. Then the Art Lead chooses 5-7 of the best ones and sends them to the producer/product owner/game designer for approval.

As a result, only one option remains, which is sent for further development.

4. Detailing and angles

This is when we start to work on the selected sketch thoroughly. The requirements for concepts are slightly different. For example, you don’t need to draw different angles for a 2D project, but the emphasis is on the final polishing of the artwork and its moving parts if there’s any animation.

In a 3D project, a 2D source plays an important role — the more detailed it is, the more accurate the game object will turn out. That is, the quality of 2D art partly determines what the final model will look like in the game.

That’s why we make sure to add several angles at this stage — from the side, from above, and from behind. The artist thinks about how everything fits together right away so the 3D artist doesn’t add any unnecessary details later. When it comes to ships, you need to make a view with closed sails where the deck is visible.

Sometimes 2D artists model their own 3D dummies to make it easier to rotate and see different angles of the model. Depending on personal preferences, this can be done in any three-dimensional package, for example, in Maya or 3ds Max.

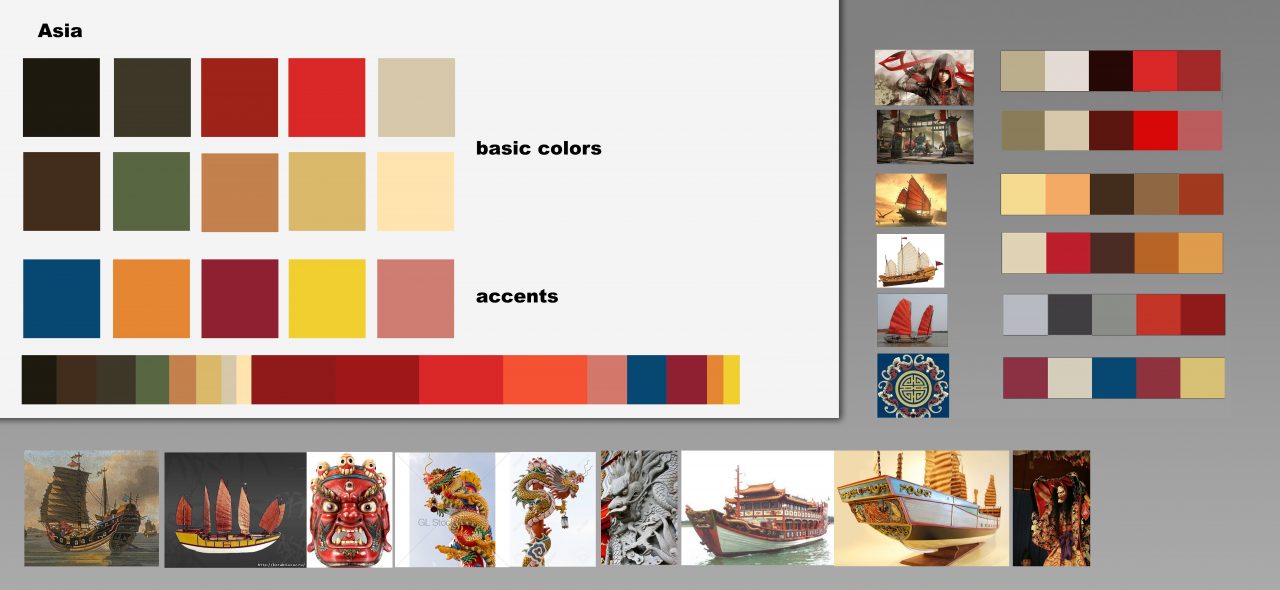

5. Color palette

The selection of colors depends on the chosen style, genre, and/or target audience. Casual players are used to a simpler and brighter palette of colors, while mid-core players want a realistic picture and detailed materials. Recently, working with colors has become even more difficult and subtle than before. Differences in player preferences and perceptions are now more individual and, for example, less dependent on things like gender: gloomy colors are no longer indicative of a game for a male audience, and pink tones don’t mean that a game will be popular only among the ladies.

The picture above is part of the faction-specific color guide. We need it to make the factions distinguishable by color at the level of primary perception. In the initial stages, the team establishes the palette for each faction, and then this document serves as a guide for all artists on the project to maintain a unified visual style.

To create a guide like this, we sort through the information within the directions we chose, look for features, historical and cultural characteristics for all factions, then break it into groups, combining them according to their characteristics. The result is the example above.

Generally speaking, color greatly affects the overall look & feel of the project. Need more visual accents? Make contrasting colors so the elements stand out. In China, a project may not be allowed into the stores at all if it features blood — you need to change the colors, and sometimes the effects entirely.

6. Final rendering

At the concept stage, the artist can just stain the entire model with colors — yellow, brown, green. But in this case, it won’t be clear what material it’s supposed to be — gold, wood, or maybe fabric.

That’s why the artist gives a certain color the properties of a certain material at the rendering stage. In other words, they finalize the model: add highlights, roughness, shadows, wood or iron, and so on. To speed up the work, it’s important the artist uses (or creates) a premade base of textures, pre-configured filters, or even 3D materials that correspond to the visual style. It’s also a perfect time to flaunt one’s photobashing skills.

After that, the finished 2D artwork goes into the hands of a 3D artist who creates an in-game model based on it. This process has its own pipeline.

However, a 2D artist’s work doesn’t end there. In addition to creating new content, projects are constantly undergoing tests and experiments. Not only with gameplay but also with the artwork.

Sometimes, during active project operations, the artwork has to be completely redrawn. The difficulty ranges from changing the character’s clothes or pose to radically rethinking the model because the players didn’t like it and the metrics prove it.

7. Working with illustrations

Illustrations that won’t become actual in-game 3D models are made more elaborate and detailed by default. Such artwork is often used in promotional materials, stores, or on game loading screens.

When creating it, you need to think deeply about the visual narrative and correctly build the composition in the frame — a single picture should tell the players what’s happening in the game and make them interested. To do this, the artist builds layouts and lighting, places color accents, and sometimes even comes up with a narrative. 3D packages help speed this process up.

Another situation is when the artwork is set to become a part of the game, for example, a 2D character for the tutorial. The final version needs to be worked out more carefully and more detailed than the concept because that’s what the player will see. It’s important to pay the most attention to the character: find and convey the right emotion, create the right mood and make the character well-distinguishable within the interface.

Final thoughts

There are also ASO and ad creatives, which we talked about here and here. To sum things up, a 2D artist is involved at almost every stage of project development. It starts with choosing the general style at the very beginning and ends with creating marketing materials for the store when the project is already in release. This article describes only a fraction of the work a 2D artist does for mobile projects. It just so happens that we’re currently making artwork for an interesting mid-core project, which we’ll make sure to talk about in the future.